Minds Behind OR&R: Meet Environmental Scientist Laurie Sullivan

By Megan Ewald, Office of Response and Restoration

This feature is part of a monthly series profiling scientists and technicians who provide exemplary contributions to the mission of NOAA’s Office of Response and Restoration (OR&R). In our latest "Minds Behind OR&R," meet environmental scientist Laurie Sullivan.

“Whatever you accomplish, it’s never by yourself. There are always people who lift you up and help you," said Laurie Sullivan while reflecting on her career in marine science, more than 25 years of which has been with NOAA. However, in hearing Laurie’s story—which starts in California, but spans across states and continents before circling home—it’s undeniable that her work ethic and versatility were important factors too.

The youngest of six children, Laurie and her siblings grew up outside of San Francisco, California in a household full of music. Her mother loved to play the piano and “forced/encouraged” each of her children to learn an instrument. This sparked Laurie’s lifelong love of the violin. In addition to her artistic talents Laurie did well in math and science, and was accepted to University of California Berkeley.

Tragically, Laurie’s mother passed away right before she started college. With remarkable resilience she managed to mostly finance her own education and find her niche at Berkeley. By sharing a room with a friend for $75 a month, working at a pizza joint, and balancing a competitive crew team schedule with increasingly demanding classes; Laurie made it work. While Laurie initially studied microbiology, she realized it wasn't the right fit.

“I was walking to sign up for medical microbio when I walked past the algae lab, where people were laughing and chatting, totally engaged in the class. Also, as I thought about it, I decided I really wanted to be able to spend more time outside than behind a microscope, so I changed to marine biology,” she said.

The next two years were full of trips to the beach, digging in the mud, studying invertebrates, and building lasting friendships. She learned to scuba dive and took a spring class at Bodega Bay in Northern California, where she ended up working after graduation.

“I’ll never have a more beautiful office than Bodega Bay,” Laurie said, “My desk used to overlook Horseshoe Cove."

Funnily enough one of Laurie’s first projects after graduation was studying how barnacles recovered after an oil spill, foreshadowing her later career. What started out as a part-time gig collecting specimens, driving vehicles into the field, and helping out in the lab soon went full-time doing toxicology work.

“I learned so much at that lab, it was such a special place, but I also knew I wanted to travel."

And so the Californian took off for the Pacific, planning to go to Australia, New Zealand, and Fiji. In Australia, she volunteered at the Australian Institute of Marine Science sorting cores from mangrove forests, then joined some field work on the Great Barrier Reef.

“It was beautiful, we got to dive at these incredibly remote places that most people never get to see” said Laurie. While studying the larval development of crown-of-thorns starfish she got the chance to dive during a soft coral spawning—a dazzling event that occurs just once a year and looks like an underwater snowstorm.

After returning from her adventures abroad Laurie headed back to Bodega Bay, taking graduate classes at Moss Landing, but soon jumped at the chance to complete her masters at Dauphin Island Sea Lab in Alabama. That work took her to Belize for her research on the offshore mangrove islands. After graduate school, she won a coveted Knauss Sea Grant fellowship in Washington D.C. where she first met several other young scientists that she still works with today.

It was during her Knauss Fellowship that Laurie first became interested in the Endangered Species Act and worked at the interface of science, policy, and people. Always a West Coaster at heart, her first federal position was working with protected salmon and several high-profile projects. Laurie credits this position for teaching her how to mediate between diverse teams of researchers as they worked on complex scientific topics, a skill that would become essential for her role at OR&R.

Despite enjoying her time working at NOAA Headquarters, eventually this Californian found herself wanting to go back where the salmon are. She took a job in San Francisco with HAZMAT, the predecessor to the Office of Response and Restoration where she worked on hazardous waste sites cleanups and settlements for NOAA at the EPA office there.

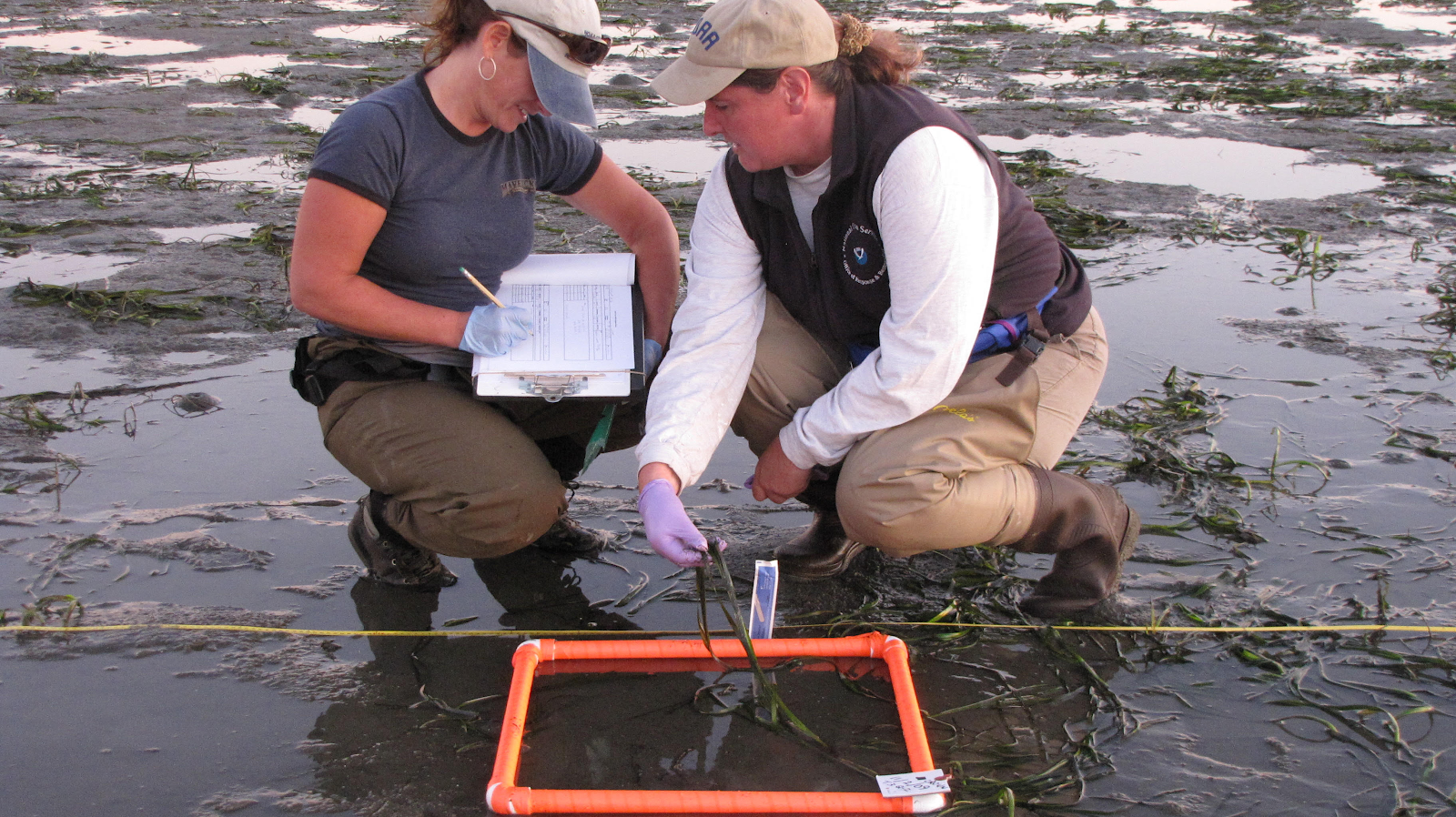

As Laurie shifted into her current position working in natural resource damage assessment across California and the Pacific Islands, she put down roots in Santa Rosa’s beautiful wine country. Perhaps the greatest challenge of her career was during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010, which called her back to the Gulf of Mexico and endangered species.

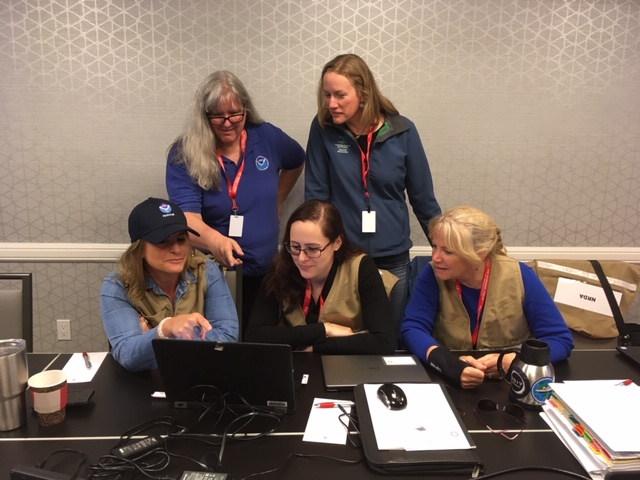

Laurie led the group assessing impacts of the historic oil spill to marine mammals—a massive undertaking that encompassed a large team of scientists from diverse backgrounds. With scientific expertise and diplomatic savvy, Laurie organized teams that implemented a comprehensive assessment and yielded an unprecedented amount of data. This work was critical in reaching the historic $8.8 billion settlement with BP to restore the Gulf of Mexico.

Over the last 10 years Laurie has continued to be an invaluable asset to OR&R's Assessment and Restoration Division, with recent accomplishments including co-authoring the technical memo Guidelines for Assessing Exposure and Impacts of Oil Spills on Marine Mammals, and working to reach a $22.3 million settlement to restore natural resources injured by the Refugio Beach oil spill in March of this year.

“What I love most about this job is being able to apply science and devise new methods. Seeing restoration come from it is so gratifying, and I work with a great, dedicated, group of people,” Laurie said.

Today, Laurie continues to enjoy the beautiful weather and scenery of Santa Rosa. She spends her free time playing the violin in several different group—and she’s not the only member of her household to enjoy classical music. Shubert, the rescue cat, got his name because of his enthusiasm for the Austrian composer. In a house full of music in the hills of California, this story comes full circle.

more images

An official website of the United States government.

An official website of the United States government.