Mysterious Oil Spill Traced to Vessel Sunk in 1942 Torpedo Attack

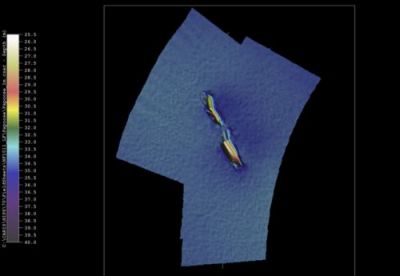

AUGUST 4, 2014 -- A few weeks ago a North Carolina fisherman had a sinking feeling as he saw "black globs" rising to the ocean surface about 48 miles offshore of Cape Lookout. From his boat, he also could see the tell-tale signs of rainbow sheen and a dark black sheen catching light on the water surface—oil. But looking around at the picturesque barrier islands to the west and Atlantic’s open waters to the east, he couldn’t figure out where it was coming from. What was the source of this mysterious oil? Describing what he saw, the fisherman filed a pollution report with the U.S. Coast Guard. On July 17, 2014, a U.S. Coast Guard C-130 aircraft flew over the site and confirmed the presence of a sheen of oil in the same vicinity. Based on the location and persistence of the sheens, the responders suspected the oil possibly could be leaking from the sunken wreck of the steamship W.E. Hutton, 140 feet below the water surface. Shortly after, archeologists confirmed that to be the case.

At the Bottom of the Graveyard of the Atlantic

This area off of North Carolina’s Outer Banks is known as the Graveyard of the Atlantic. The combination of harsh storms, piracy, and warfare have left these waters littered with shipwrecks, and because of the conditions that led to their demise, many of them are broken in pieces. In the midst of World War II, on March 18, 1942, the W.E. Hutton was one of three U.S. vessels in the area torpedoed by German U-boats. Tragically, 13 of the 23 crew members aboard the ship were killed. The Hutton’s survivors were rescued by the Port Halifax, a British ship. When the steam-powered tanker was hit by German torpedoes, the Hutton was en route from Smiths Bluff, Texas, to Marcus Hook, Pennsylvania, with a cargo of 65,000 barrels of #2 heating oil. An initial torpedo hit the starboard bow, and the second hit to the port side came 10 minutes later. The ship sank an hour after the first hit, eventually settling onto the seafloor. Today, it is reportedly upside down, with the port side buried in sand but with the starboard edge and some of its railing visible. The wreck of the W.E. Hutton also is located in the NOAA Remediation to Undersea Legacy Environmental Threats (RULET) Database. Evaluated in the 2013 NOAA report “Risk Assessment for Potentially Polluting Wrecks in U.S. Waters,” this wreck was considered a low potential for a major oil spill because dive surveys “show all tanks open to the sea and no longer capable of retaining oil." However, as the fisherman could observe from the waters above, some oil clearly remains trapped in the wreckage. This shipwreck was described by wreck diver and historian Gary Gentile as having “enough large cracks to permit easy entry into the vast interior.” Another wreck diver and historian, Roderick Farb, noted that the largest point of entry into the hull is “about 150 feet from the stern,” through a “huge crack in the hull full of rubble, iron girders, twisted hull plates and other wreckage.” This wreck is the closest one to the spot where the fisherman first saw the leaking oil, and given the Hutton’s inverted position and such cracks, we now realize the possibility that the inverted hull has been trapping some of the 65,000 barrels of its oil cargo as well as its own fuel.

Solving the Problems with Sunken Shipwrecks

On July 21, 2014, a commercial dive company contracted by the U. S. Coast Guard sent down multiple dive teams to the Hutton’s wreck to assess the scope and quantity of the leaking oil. The contractor developed and implemented a containment and mitigation plan, which stopped the flow of oil from a finger-sized hole in the rusted hull. It is not known how much oil escaped into the ocean or how long it had been leaking before the passing fisherman noticed it in the first place. NOAA's Office of Response and Restoration, led by Scientific Support Coordinator Frank Csulak, provided the U.S. Coast Guard access to historical data about shipwrecks off of North Carolina, survey information, including underwater and archival research, and the animals, plants, and habitats at risk from the leaking oil. Our office frequently provides scientific support in this way when a maritime problem occurs due to sunken wrecks. They may pose a significant threat to the environment, human health, and navigational safety (as an obstruction to navigation). Or, as in this case, shipwrecks can threaten to discharge oil or hazardous substances into the marine environment. Last May, our office released an overall report describing this work and our recommendations, along with 87 individual wreck assessments. The individual risk assessments highlight not only concerns about potential ecological and socio-economic impacts, but they also characterize most of the vessels as being historically significant. In addition, many of them are grave sites, both civilian and military. The national report, including the 87 risk assessments, is available at “Potentially Polluting Wrecks in U.S. Waters.” Several of those higher-risk wrecks also lie in the Graveyard of the Atlantic, but as we discovered, it is difficult to predict where and when a rusted wreck might release its oily secrets to the world.

An official website of the United States government.

An official website of the United States government.