Minds Behind OR&R: Meet Marine Biologist Gary Shigenaka

This feature is part of a monthly series profiling scientists and technicians who provide exemplary contributions to the mission of NOAA’s Office of Response and Restoration (OR&R). This month’s featured scientist is Gary Shigenaka, a marine biologist in OR&R’s Emergency Response Division.

Marine biologist Gary Shigenaka has been interested in science and biology for as far back as he can recall. Growing up in Illinois, he was the type of kid who spent his free time collecting frog eggs to hatch into tadpoles, and monarch butterfly caterpillars to watch their transformation. He would bring home snakes from campouts, and delight in each new discovery of a nest of cottontail rabbits in the field.

“As cool as all of that was, it seems like many marine scientists of my ageing generation, I was totally seduced by television, and ‘The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau’,” Gary said. “Tadpoles were fascinating, but the stuff that Cousteau introduced me and so many others to was a saltwater world that was seemingly more complex, and colorful, and jaw-dropping.”

Gary is a third generation Japanese American, or “Sansei.” His family first came over from Japan in the early 20th century, when his maternal grandmother arrived in the U.S. by way of Seattle. Her original destination was San Francisco, but after the great earthquake that hit Northern California in 1906 she altered course for the Pacific Northwest.

Though his family’s roots in America began on the West Coast, Gary grew up in Chicago. His father had been among the thousands of Japanese Americans forced into internment camps during World War II. His release was granted only under the condition that he move further inland for work. His father worked as a cook at a private hospital in suburban Chicago, where he rose to become the head chef. His mother worked hard raising her two sons, and later became a nursery school teacher. Though no one in his family came from a science background, Gary said his parents’ hard work and support facilitated his pursuit of a career spent in and around the ocean.

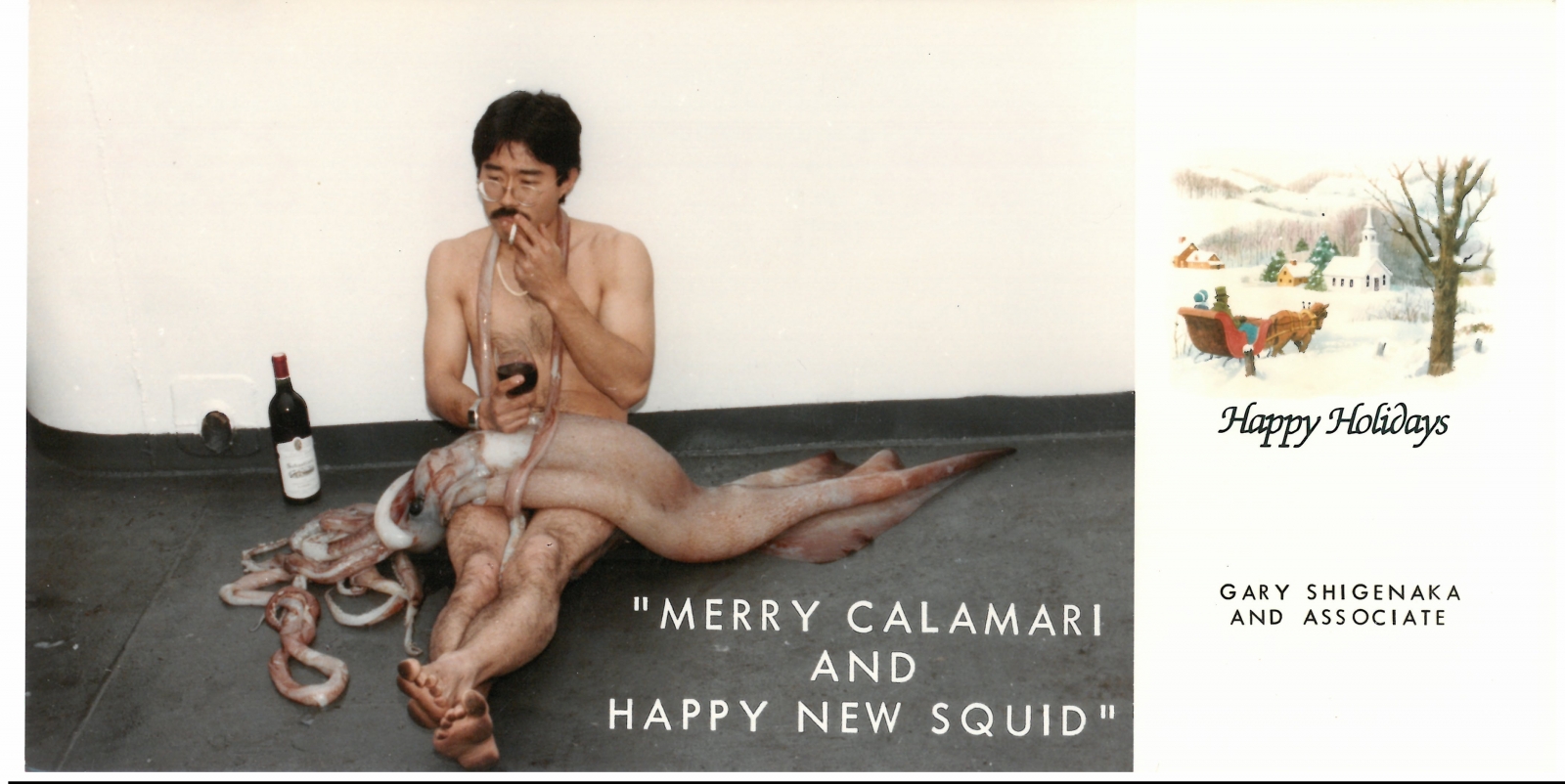

Growing up in Chicago, Gary’s opportunities for ocean-related exploration were limited. But at the age of 5, he had his first real-life encounter with the saltwater shores of southern California. His father used to take 8 mm movies of the family. He was able to catch Gary’s first ocean exposure on camera, showing him in a Pacific tide pool with an octopus wrapping its tentacles around his arm.

Gary’s interest in the ocean continued to grow throughout high school and into college as he went on to study oceanography at the University of Washington in Seattle. After graduating in 1976, Gary worked as a bartender in Seattle’s Pioneer Square. At the time, jobs were scarce for the new graduates who studied biology or environmentally-related issues. But he eventually got his start in the field working a temporary position for the Washington Department of Fisheries doing salmon research in the Puget Sound.

Around the time his temporary position was wrapping up, the U.S. and many other countries were extending their coastal territorial authorities from 3 miles to 200 miles — meaning that many fisheries that had been in international waters were now under U.S. jurisdiction and management. As those fisheries transitioned from foreign harvesting to U.S. domestic, there were requirements for American observers to be placed aboard foreign fisheries vessels operating in the newly extended fisheries zones. The National Marine Fisheries Service needed foreign fisheries observers to make sure foreign fleets were fishing in permitted areas, and to verify their catch.

Gary signed up to be an American observer aboard a Japanese crab factory ship operating in the Bering Sea, where he would remain aboard the ship until the U.S.-determined catch quota was filled, which was estimated to take six months.

“On the surface, this didn’t seem so bad. But this factory ship never went in to port. Six months at sea was really six months at sea, and in this case, the Bering Sea,” Gary said. “But what the heck, a free trip to and from Japan, a regular (if meager) paycheck, and an adventure. If you ignore the similarities to being incarcerated — being constrained to a 400- to 500-foot space, with 300 to 400 men, and not even a remote possibility of stepping onto land, it was OK.”

Gary spent two seasons aboard the ship. He then applied for positions with NOAA and landed another temporary position helping with ichthyoplankton research in the Gulf of Alaska — eventually leading him to the NOAA Fisheries research ship, the Miller Freeman.

“When my time was up, I was about to depart the ship and fly back to Seattle, when the Miller Freeman offered me a job as a deckhand and a quartermaster.,” Gary said. “And as was often my response to many opportunities that presented themselves back in those days, my attitude was, ‘why not?’”

Gary did a six-year stint as a crew member aboard the vessel. He eventually moved to the biological survey technician’s department, which supported the scientific parties that came aboard the ship. While aboard the Miller Freeman, Gary began to realize that he would always be collecting data for someone else’s research if he didn’t go back to school.

So with the blessing of his NOAA Corps ship’s captain and operations officer, Gary applied for and received agency support in returning to graduate school. While working on his master’s degree at the University of Washington’s School of Marine Affairs — under the tutelage of former director, Dr. Tom Leschine — he began to narrow his focus to environmental issues associated with the ocean.

After choosing a thesis topic on nonpoint source pollution in Puget Sound waters, he applied for and was awarded a Sea Grant Fellowship in Washington D.C. through a program that would later be named the John A. Knauss Marine Policy Fellowship Program. He was placed into a nationwide coastal environmental monitoring program and served a one-year fellowship there, collecting samples in the field aboard NOAA ships, and then analyzing the data to provide the basis for evaluating the health of coastal habitats and resources around the country. When his year was up, the office gave him an offer to continue the job.

As much as he enjoyed the work, Seattle is where his heart is. He applied for and was offered a job with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and another with NOAA in the regional office of the program he had worked for in D.C.

“I opted for NOAA, in no small part because I felt both allegiance and gratitude for its support in allowing me to go back to grad school,” Gary said.

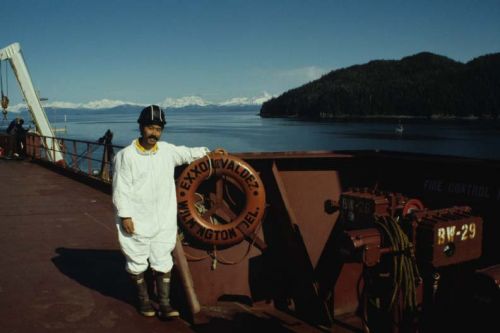

Gary continued working on studies that compared marine environmental quality in specific regions of the country until March 1989 when the Exxon Valdez tanker grounded in Alaska’s Prince William Sound, spilling nearly 11 million gallons of oil. At the time, it was the largest oil spill in history. It was an all hands on deck situation.

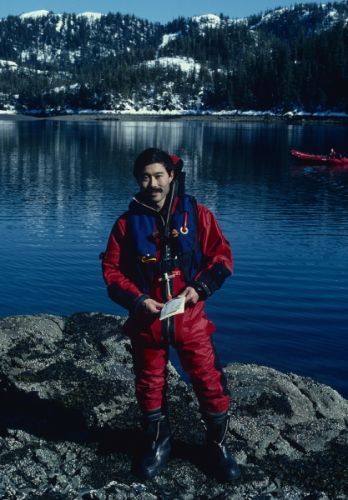

Gary’s office was down the hall from the NOAA Hazardous Material Response Division (HAZMAT), the precursor to what is now the Office of Response and Restoration’s Emergency Response Division. With other scientists from his group, Gary worked aboard a specially outfitted NOAA ship to conduct damage assessment studies in the spill-affected area. Working with other researchers from the National Marine Fisheries Service, he collected and analyzed sediment, water, and fish samples in Prince William Sound and other Alaskan waters impacted by oil.

Following the first year of the Exxon Valdez response, Gary was invited to join HAZMAT along with two of his colleagues, Alan Mearns and Rebecca Hoff.

“We became charter members of the biology team for HAZMAT, which prior to that point had been comprised mostly of modelers, computer programmers, and logistical support specialists,” Gary said.

In his current role at OR&R, Gary provides scientific support to the U.S. Coast Guard and other agencies during spills of oil and hazardous chemicals, specifically biological support, which means just about anything to do with plants, animals, and habitats that might be affected by releases of oil and chemicals.

“I enjoy the challenge of dealing with a broad range of biological issues spanning many disciplines, and I also like performing applied science. That is, just about everything we study ourselves or read in the scientific literature is interpreted through the lens of the real world of spill response,” Gary said. “Ultimately, that means that we are trying to use scientific knowledge to minimize or reduce environmental harm. It also means that the answers we give to questions have consequences that we often can see, for better or worse.”

In his free time, Gary enjoys planting and growing unusual, or novel, trees and plants. He is currently growing trees in Seattle from seeds of the Kazakhstan apple seeds thought to be the progenitor of all domestic apples from a university agricultural research center. He is expecting his first fruit this year.

“My interest in so-called heirloom, heritage, or legacy plants is more tied into the history of where they and we came from, and a concern that large-scale manipulation of the plants that form the base of our food chain is diluting one of our important heritages,” Gary said.

He is also growing beans in his garden that are allegedly from seeds found in Native American pottery; red corn from South Carolina that nearly vanished but was saved by whisky distillers there; and tomatoes from a food tour he took in Barcelona several years ago.

Gary’s father instilled in him, or “cursed” him with, a love of baseball. While it took some time for team allegiances to shift from Chicago to Seattle, he is now a Seattle Mariners fan. And like an inherited disorder, Gary’s son now carries that burden — he works for the baseball team as a business analyst. Gary and his son Mason just returned from Cooperstown, New York, where they helped celebrate the induction of Mariner great Edgar Martinez into the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

The Seattle area is home for Gary, who also maintains a cabin in the San Juan Islands near the Canadian border. “I love the Pacific Northwest, with its mix of saltwater, and mountains, and mild temperatures. However, I grow increasingly concerned as our climate rapidly changes, our snowpack vanishes, river flows diminish and native salmon suffer, and the clear summertime skies are sullied by smoke from the increasing occurrence of wildfires all over the West. Complacency is no longer an option,” he said.

more images

An official website of the United States government.

An official website of the United States government.