NOAA Tracks Path of Possible Japan Tsunami Dock off Washington Coast

UPDATED JAN. 18, 2013 — The Japanese Consulate has confirmed to NOAA and our partners that the large floating dock that washed ashore in Washington's Olympic National Park in late December is in fact one of three* docks missing from the fishing port of Misawa, Japan, which were swept away during the March 2011 Japan tsunami.

UPDATED JAN. 7, 2013 — The dock remains beached on the Olympic Peninsula of Washington as state responders continue developing a plan to remove the large item.

Washington State Department of Ecology reports: "As a precaution, a tracking buoy is attached to the dock. The buoy transmits its location twice daily via satellite ... A small group of responders was able to reach the dock on Friday, Dec. 21. Working quickly during this month's last daytime low tide, the team thoroughly measured and inspected the dock, collected samples of the marine organisms clinging to it and placed the tracking beacon on it."

DEC. 21, 2012 — For NOAA oceanographers working in pollution response, part of their job is to predict where pollutants (mostly oil) spilled into the ocean will end up.

Sometimes that means they are asked to forecast possible paths, or trajectories, for other objects spotted at sea—such as a large dock recently reported to be floating off the coast of Washington state, approximately 16 nautical miles northwest of Grays Harbor.

We suspect—though we are still waiting for confirmation—that this dock began its oceanic journey in March of 2011 at the Port of Misawa, Japan, following the devastating Tōhoku earthquake and subsequent tsunami. Three* docks were ripped away from this port.

After approximately 15 months at sea, one of the docks turned up on Agate Beach near Newport, Ore., in June 2012. A second dock suspected** to be from Misawa was spotted offshore of the Hawaiian Islands in September. The vast difference in the paths of these three docks is a good illustration of how turbulent ocean currents and winds can scatter widely objects floating at sea.

When this latest dock was spotted on Friday, December 14, we at NOAA were asked to forecast where winds and currents might move the dock over the next few days. The dock is a large, unlit, concrete structure and hence posed a significant hazard to navigation.

Furthermore, with stormy weather and strong onshore winds in the forecast, it seemed likely the dock would end up on the beach. Many beaches along the northern Washington coast are quite remote, varying from sandy or rocky beaches to cliffs dropping right down to the water. Depending on where the dock came ashore, access could prove difficult and might allow possible invasive species hitching a ride on the dock time to spread into local ecosystems. To be better prepared to take action, we needed to know where and when the dock might come ashore so it could be located quickly.

In order to predict the trajectory of an object floating at sea, we require forecasts of winds and ocean currents. Many of you may be familiar with the difficulty involved in predicting the weather. Although weather forecasts are generally reliable for the first few days of a forecast period, a forecast always contains some uncertainty which tends to increase over time. For example, this weekend’s weather forecast is generally more accurate than next weekend’s forecast.

Forecasting ocean currents faces similar difficulties, which may be compounded by a lack of observations. There are few (if any) direct measurements of real-time ocean currents on the Washington coast. In addition, there is further uncertainty about how a floating object such as a large dock will move in response to the currents and winds. For example, an object that is floating high in the water will "feel" the winds more than an object floating lower in the water. While we could estimate this effect for the dock, it adds another source of uncertainty to the mix.

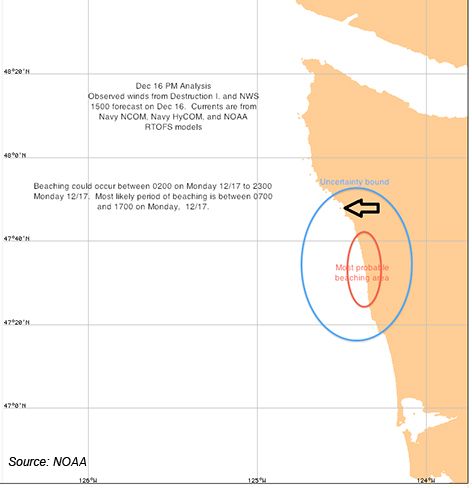

So what can we do with all this uncertainty when "I don't know" is not an acceptable answer? The approach we took was twofold. In addition to providing a "best estimate" trajectory for the dock, in which we considered the wind and currents forecasts as truth, we also ran multiple scenarios in our trajectory model to determine where else the dock possibly could end up. These additional scenarios might use different values approximating how much the dock gets pushed along like a sailboat or they might adjust the wind and current forecasts slightly to see how this affects the projected path of the dock. After running the trajectory model multiple times, we produced a map that indicated the most likely area that the dock would come ashore, but the map also included a larger area of uncertainty around it (an "uncertainty boundary") where the dock might be found if, for example, the currents were stronger than predicted.

Because the dock was not spotted again after the initial report on December 14, our trajectory could only narrow down the search area to an approximately 50 mile stretch of the Washington coast (remember, forecast error grows with time).

However, using the forecast guidance, state, federal, and tribal representatives mobilized search teams, and the dock was located on the afternoon of December 18 by a Coast Guard helicopter aerial survey. The dock had been washed ashore, most likely sometime during the evening before, on a rugged stretch of coastline north of the Hoh River. Access to the region is difficult, but personnel from the National Park Service and Washington State Fish and Wildlife are attempting to reach the dock to sample it for invasive species and to attach a tracking buoy in case it refloats before it can be salvaged.

Here you can see an example animation of our trajectory model GNOME showing a potential path of the dock. Particles are released in the model at the position where the dock was initially sighted. The particles move under the influence of winds and ocean currents. They also spread apart over time; this is simulating the small-scale turbulence in the winds and currents. This particular scenario was run after the dock was stranded and uses observed winds from a nearby weather station (wind direction and strength is shown by the arrow on the upper right) and a northward coastal current of approximately 1 knot.

Download the video file of the dock's projected trajectory. [.MP4, 156 KB]

*[UPDATE 4/5/2013: This story originally stated that four docks were missing from Misawa, Japan and that "one of the four turned up several weeks later on an island south of Misawa." We now know only three docks were swept from Misawa in the 2011 tsunami, and none were found on a Japanese island.]

**The dock near Hawaii has not been confirmed by the Japanese Consulate as being from Misawa.

An official website of the United States government.

An official website of the United States government.