How NOAA Uses Coral Nurseries to Restore Damaged Reefs

DECEMBER 5, 2014 -- The cringe-inducing sound of a ship crushing its way onto a coral reef is often the beginning of the story. But, thanks to NOAA's efforts, it is not usually the end. After most ship groundings on reefs, hundreds to thousands of small coral fragments may litter the ocean floor, where they would likely perish rolling around or buried under piles of rubble. However, by bringing these fragments into coral nurseries, we give them the opportunity to recover. In the waters around Florida, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, NOAA works with a number of partners in various capacities to maintain 27 coral nurseries. These underwater safe havens serve a dual function. Not only do they provide a stable environment for injured corals to recuperate, but they also produce thousands of healthy young corals, ready to be transplanted into previously devastated areas.

Checking into the Nursery

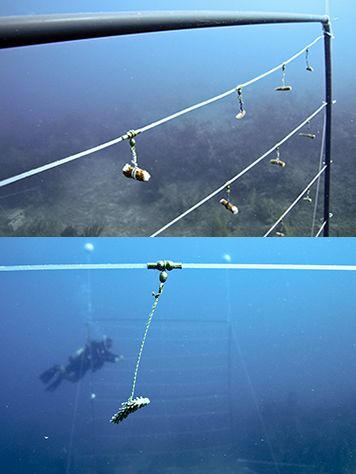

When they enter coral nurseries, bits of coral typically measure about four inches long. They may come from the scene of a ship grounding or have been knocked loose from the seafloor after a powerful storm. Occasionally and with proper permission, they have been donated from healthy coral colonies to help stock nurseries. These donor corals typically heal within a few weeks. In fact, staghorn and elkhorn coral, threatened species which do well in nurseries, reproduce predominantly via small branches breaking off and reattaching somewhere new. In the majority of nurseries, coral fragments are hung like clothes on a clothesline or ornaments on trees made of PVC pipes. Floating freely in the water, the corals receive better water circulation, avoid being attacked by predators such as fireworms or snails, and generally survive at a higher rate. After we have established a coral nursery, divers may visit as little as a few times per year or as often as once per month if they need to keep algae from building up on the corals and infrastructure. "It helps if there is a good fish population in the area to clean the nurseries for you," notes Sean Griffin, a coral reef restoration ecologist with NOAA. Injured corals generally take at least a couple months to recover in the nurseries. After a year in the nursery, we can transplant the original staghorn or elkhorn colonies or cut multiple small fragments from them, which we then use either to expand the nursery or transplant them to degraded areas. One of the fastest growing species, staghorn coral can grow up to eight inches in a year while elkhorn can grow four inches. We are still investigating the best ways to cultivate some of the slower growing species, such as boulder star coral and lobed star coral.

Growing up to Their Potential

In 2014, we placed hundreds of coral fragments from four new groundings into nurseries in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. This represents only a fraction of this restoration technique's potential.

After the tanker Margara ran aground on coral reefs in Puerto Rico in 2006, NOAA divers rescued 11,000 salvageable pieces of broken coral, which were reattached at the grounding site and established a nursery nearby using 100 fragments from the grounding. That nursery now has 2,000 corals in it. Each year, 1,600 of them are transplanted back onto the seafloor. The 400 remaining corals are broken into smaller fragments to restock the nursery. We continue to grow healthy corals in this nursery and then either transplant them back to the area affected by the grounded ship, help restore other degraded reefs, or use some of them to start the process over for another year. Nurseries in Florida, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands currently hold about 50,000 corals. Those same nurseries generate another 50,000 corals which we transplant onto restoration sites each year. Sometimes we are able to use these nurseries proactively to protect and preserve corals at risk. In the fall of 2014, a NOAA team worked with the University of Miami to rescue more than 200 threatened staghorn coral colonies being affected by excessive sediment in the waters off of Miami, Florida. The sedimentation was caused by a dredging project to expand the Port of Miami entrance channel. We relocated these colonies to the coral nurseries off Key Biscayne run by our partners at the University of Miami. The corals were used to create over 1,000 four-inch-long fragments in the nursery. There, they will be allowed to recover until dredge operations finish at the Port of Miami and sedimentation issues are no longer a concern. The corals then can either be transplanted back onto the reef where they originated or used as brood stock in the nursery to propagate more corals for future restoration.

An official website of the United States government.

An official website of the United States government.